How Field’s middle school students develop an internal compass they'll use for life.

Written by Middle School Director Gil Gallagher

I still remember the compass clipped to my childhood backpack—a transparent plastic plate with a black dial suspended in liquid, always pointing north. I rarely used it for actual navigation in the city (I was a bike kid who knew every shortcut and quiet street), but that compass became essential during my intentional adventures getting lost in Rock Creek Park.

We knew the park ran north to south, and that heading west would always lead us back to civilization. That simple tool gave us the confidence to explore.

A compass is a powerful tool—and a powerful metaphor, especially for middle school. This same principle of internal navigation guides our approach to middle school education at Field.

At our first middle school meeting of the year, I experimented with our students and faculty. I asked everyone to close their eyes and point "up." Easy—everyone's hands pointed confidently toward the ceiling. I reminded them that our vestibular system, when functioning properly, pretty much guarantees that we can orient ourselves towards the sky and the center of the Earth.

Then, with their eyes open, I asked them to point north.

Hands across the room spun like compass needles at the magnetic pole.

Watching students during moments like these reveals something important: bright, capable kids can feel completely lost when the familiar markers disappear. Some students peered out windows, searching for familiar landmarks. Others tried to reconstruct their morning commute. Many looked around the room, hoping to align with the majority. A few just looked at me, waiting for the answer.

I didn't give them one. Because in that moment, it wasn't about knowing which way was north—it was about learning how to know, which is, at its core, what we do in Middle School at Field.

Here is the unique challenge and opportunity of middle school: students are developing their own system of decision-making. It's no longer enough to follow elementary school rules or rely on their parents for every choice. They need their own internal compass.

Often, I point our students towards Field’s core values—the ideas that serve as cardinal directions for our School’s decision-making: creativity, connection, reflection, resilience, inquiry, and inclusion. These aren't abstract concepts but practical tools children can use every day to navigate friendships, academic challenges, and personal growth.

I also encourage students to "look for the helpers," wisdom I gleaned from the late Fred Rogers, one of my personal heroes. Mr. Rogers dedicated his life to listening to and honoring the perspectives of young children.

Middle schoolers encounter increasingly complex social situations—from playground disputes that become more sophisticated to early discussions about identity, fairness, and current events. We teach students that they don't need to choose performative extreme positions or get swept up in "us versus them" thinking.

I point our students towards our guidelines for polarizing conversations to ground them, unpacking the word "polarizing" for them, which is a challenging idea to grasp.

In a conversation with Debario Fleming, our Director of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, he half-jokingly wondered if many of our students thought that polarizing conversations were about bears. So I asked our students where polar bears lived, and after sorting through some misconceptions about polar bears in Antarctica, we agreed that polar bears are called "polar" bears because they live near the North Pole.

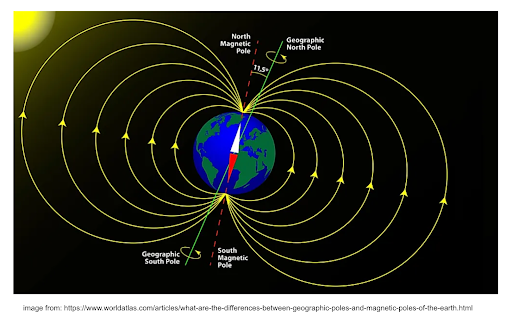

So I showed students this diagram:

And I reminded them that:

Simple exercises like this help children understand that they can hold nuanced views, ask questions, and change their minds as they learn—skills they'll need in high school, college, and beyond.

Our faculty work hard to create opportunities for students to engage in challenging conversations and to build environments and classroom communities where students can take risks. Stepping into spaces of discomfort requires courage and trust, which are essential for orienting our students to our community of learning. Here are a few things that our middle school teachers do to help compass-building across our curriculum:

All of these approaches work toward a common goal: to build trust, confidence, and courage that our students need to engage authentically with challenging material, complex social situations, and learn who they want to become.

Here's what we hope for our students: that they develop the confidence to get intellectually "lost"—just like I did exploring Rock Creek Park as a kid.

They learn to tackle challenging problems, engage in difficult conversations, and explore unfamiliar ideas because they trust their ability to find their way back to solid ground. When students know their values, can identify their helpers, and recognize that they can handle uncertainty, they embody what we call informed courage. This is an important skill children need to possess to thrive in high school, college, and the rapidly changing world they'll inherit.

When students transition from one grade level to another, our expectations shift because our curriculum builds towards higher levels of sophistication. As children grow, their minds become more capable of handling abstraction, ambiguity, and juggling different responsibilities.

As a parent, you're watching your child develop independence while still needing your guidance, which can feel unsettling. You might wonder: Are they ready for this much responsibility? Will they make good choices?

With the proper support, they are ready. Middle school is the perfect time for students to develop their own internal compass. Just as I clipped that plastic compass to my backpack as a child, our students learn to carry these tools with them—the core values, the conversation guidelines, the trust they've built with helpers.

And, like my childhood adventures in Rock Creek Park, sometimes the most important learning happens when students allow themselves to get intentionally lost, knowing they have the tools to find their way back to something meaningful.